Baroque music has this special charm—ornate, emotional, and precise. And no one brings it to life quite like Trevor Pinnock. Whether it’s Bach, Handel, or Vivaldi, Pinnock’s recordings always have that signature balance of energy and elegance.

But have you ever wondered how one of his iconic Baroque albums actually comes together? Let’s step inside the studio and look into the fascinating journey from sheet music to final recording.

Preparation

Everything starts way before anyone hits “record.” Preparation is the backbone of any Trevor Pinnock recording. He doesn’t just show up and wave a baton—this is where months of planning begin.

First, there’s the repertoire selection. Pinnock dives deep into the music, sometimes choosing lesser-known pieces to highlight Baroque gems that deserve the spotlight. He studies original manuscripts, historical performance notes, and even old treatises to understand exactly how the music was intended to be played.

Then comes the ensemble. Pinnock usually works with period instrument orchestras, like The English Concert, which he founded. Each musician is carefully chosen not just for skill, but for how well they understand Baroque style and historically informed performance.

Instruments

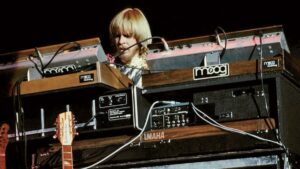

Baroque music isn’t played on your average modern violin or flute. Trevor Pinnock’s recordings always feature period instruments—those built or modeled after ones from the 17th and 18th centuries.

Why does that matter? These instruments produce a completely different sound. A Baroque violin, for example, uses gut strings and has a softer, warmer tone than its modern cousin. Harpsichords replace modern pianos. Natural trumpets (with no valves!) require incredible skill and breathe authenticity into the recording.

Instruments are often tuned to a lower pitch standard too—usually A=415 Hz instead of today’s A=440 Hz. This small tweak creates a richer, darker sound that brings out the character of the Baroque period.

Rehearsals

Once the musicians and instruments are in place, it’s time to rehearse. But this isn’t your typical run-through. Under Pinnock’s direction, rehearsals are like musical archaeology—digging deep into the phrasing, ornamentation, and tempo choices.

Baroque music leaves a lot to interpretation, and Pinnock encourages musicians to use their imagination. There are discussions about whether a trill should start on the upper note or the main note, or how long a fermata should be held. Everything is fair game, as long as it serves the music.

These rehearsals are both intense and collaborative. Pinnock leads, but he listens, too. The atmosphere is one of shared exploration, where each musician contributes their expertise.

Recording

Now comes the moment of truth: the actual recording sessions. This is usually done in an acoustically perfect hall or church, often chosen for its natural reverberation. Think warm wood, high ceilings, and echo-friendly architecture.

Pinnock prefers live recording takes when possible. That means full runs of entire movements, capturing the natural energy and flow of a live performance. It’s risky—any slip means doing it all again—but it’s worth it for the authenticity.

Microphones are strategically placed to capture not just the sound but the spatial balance. A harpsichord might need its own mic, while strings are captured with ambient room microphones. The sound engineer plays a huge role here, working closely with Pinnock to ensure every detail is clear and emotionally resonant.

Editing

After the recording sessions wrap up, it’s time for the editing process. But don’t worry—it’s not about autotune or fake enhancements. It’s about choosing the best takes and seamlessly stitching them together if needed.

Pinnock listens carefully to each version, deciding which one captures the emotion, timing, and spirit he wants. Sometimes it means combining a first half from one take with a better ending from another. But the goal is always the same: keep the integrity of the music intact.

Post-production may also involve subtle equalization or balancing instruments in the mix, but always with a light touch. You want to hear the music, not the engineering.

Release

Once the final master is ready, it’s handed over to the label. Pinnock’s recordings are often released under prestigious classical labels like Deutsche Grammophon or Archiv Produktion.

The final steps include creating liner notes—often written by Pinnock himself or musicologists—which offer listeners historical insights and context. The cover art is carefully selected to reflect the era and feel of the recording. And then, it’s out into the world, both on physical CD and digital streaming platforms.

Here’s a quick look at the process:

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| Preparation | Repertoire selection, research, assembling musicians |

| Instruments | Period instruments tuned to Baroque standards (A=415 Hz) |

| Rehearsals | In-depth phrasing, style, and ornamentation exploration |

| Recording | Live takes in acoustic venues, mic placement, and engineer collaboration |

| Editing | Select best takes, minimal corrections, preserve authenticity |

| Release | Mastering, liner notes, artwork, distribution via label |

In the end, a Trevor Pinnock Baroque recording isn’t just a musical product—it’s a deeply thoughtful, historically grounded work of art. Each step, from the first rehearsal to the final mix, is filled with care and intention. And that’s what makes his music so timeless and powerful.

FAQs

Who is Trevor Pinnock?

He’s a British conductor and harpsichordist known for Baroque music.

What is historically informed performance?

It’s playing music using techniques and instruments from the original era.

Why use period instruments?

They create an authentic Baroque sound with different tuning and tone.

Where are Pinnock’s recordings made?

Usually in acoustic venues like churches or old concert halls.

Does Pinnock edit recordings heavily?

No, he prefers minimal edits to keep the performance natural.